Kill Your Grandparents

Here, look at this.

I don’t want to waste a crapload of time on discussing the points in this post, since their most professional support comes from an archaic ethos and amazingly selective reasoning. For more in-depth discussion, you can see Joe Abercrombie’s response or Adam Whitehead’s, both of which have made strong arguments against the article and whom I pretty much agree with. Amanda took this shit and used it as fertilizer to make a patch of daisies in this entry.

The reasons we’re not going to discuss the points offered here are twofold. As previously suggested, there’s no actual logic behind this post. It’s a man citing his opinion (which is not the worst opinion to cite) and supporting it with various No True Scotsman fallacies and tossing out vague buzzwords in the hopes that people will (and, if you don’t value your sanity enough to avoid checking the comments section, you’ll see that many do) agree with them. Beyond that, though, it boils down to an issue in fantasy that I’ve mentioned before and that I feel is worth bringing up here again.

Behold, the Tolbert Principle:

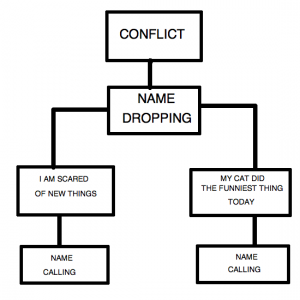

Every argument about fantasy begins and ends the same way.

It starts with the issue at hand, in this case: the idea that certain fantasy series are going beyond the pale in terms of negativity and bleak hopelessness in the name of being edgy. This is not where the problem lies. In fact, this issue has been brought up before, most notably (or, because I was too lazy to look up anyone else’s opinion on the subject and mine matters the most anyway by virtue of the fact that I am the tallest person ever) by me in this post I did for Grasping For the Wind. In the interests of summarizing: yes, it’s a valid concern that we’re pushing unrealistic darkness onto fantasy for the sake of naming ourselves edgy (anyone who has read Abercrombie, though, will probably realize that the darkness and despair fits what he’s trying to do with his work).

It’s past that point that we begin to see problems. Name Dropping follows, in which we cite people who may or may not have anything to do with the work in question and who may or may not have been striving for the same tone, mood or theme that the work in question is. Name Dropping is important, since it actually does establish valid comparison and example where applicable. Italicized for emphasis because, all too often, that part goes out the window and the argument becomes a battle of fantasy Pokemon, with people throwing out names as though Jules Verne could be summoned up from the dead, use Thundershock and strike down Robert E. Howard, thus earning the coveted Cerulean Badge and advancing to the next gym.

From that point, the argument usually boils down one of two ways, the leftmost one being the one we are discussing: too often we use the works of past authors as a means of justifying our lack of progress and this article exemplifies this perfectly. Today, people are rejecting Joe Abercrombie because he doesn’t have the True Mythic Power of an Evolved Tolkien. Tomorrow, we’re rejecting Blake Charlton because his Tackle isn’t as effective as Joe Abercrombie’s Earthquake.

The metaphor has been so tortured that he has renounced his faith and converted, so let me get to the meat of the matter.

The fact that we use so many names as a means of justifying our unwillingness to accept new ideas and embrace stagnation doesn’t point to a flaw with the people who used them. There is still plenty to learn, good and bad, from Tolkien. Howard influences the genre, still. But neither of them controls it. Nor should they. We shouldn’t be looking for “the next Tolkien.” We shouldn’t even be looking for the person who comes the closest to Tolkien. That cheapens his work, cheapens the work of authors he’s being compared to and cheapens the genre as a whole when we think there is only one story to tell.

It would be amazingly easy if I could point to this article and say “this. This is the problem with all fantasy.” But I cannot. This article is not the voice of fantasy collectively choosing to regress. This is a man who is scared of new things voicing his opinion. Fantasy readers are, as a whole, open-minded enough and wholesome enough that this is not the biggest of problems we have facing us. But at the same time, it happens enough that it’s worth talking about.

Every time we say “he’s no George R.R. Martin,” we’re doing it. Every time we say “why can’t you be more like Tolkien,” we’re doing it. Every time we say “I was really looking for something more dark swords and sorcery with a twist of new weird with a strong undercurrent rooted in epic fantasy, but this is really more fantasy romance/fantasy allegory with strong tones of the optimistic epic and prophecy as foretold by Salzman” we do it.

…okay, so I’m the only one who’s ever actually said that, but the point remains: we cannot use names as a means of justifying fear. If anything, fearless should be our watchword.

As writers, we should not feel bound by traditions and terrified of stepping outside the territories paved by previous authors.

As readers, we should not feel obligated to dislike anything that takes us outside of our comfort zone or takes us into new situations that we’re not always prepared to deal with.

We will try to fly. Sometimes, we will take wing. Sometimes, we will crash. But this being a genre based on “what if,” when we crash, we will do so fantastically and we will use the smoldering ruin and charred corpses as a take-off point for the next one.

And every time you feel the need to regress and retreat, go click on that link. Go read that article. Go read the comments. Find the one where someone suggests that women and their “desire for debasement” have ruined fantasy.

And think “that could be me.“

Kill Your Grandparents Read More »